Daria Parkhomenko is the founder and director of LABORATORIA, an Art and Science Foundation based in Moscow, Russia. For the last ten years the foundation has promoted a dialogue at the intersection of Art and Science, realised as exhibitions, international collaborations, symposiums and conferences. Following the successful Daemons in the Machine exhibition, which presented works related to Artificial Intelligence and society, I spoke with Daria about the concepts driving the exhibition and her views on AI and Art.

Can you tell us about the curatorial ideas behind the “Daemons in the Machine” exhibition?

From the very beginning in 2008, LABORATORIA’s practice has been driven by deep interaction with scientists. In discussions with them we seek to understand real, relevant scientific problems and their speculative ideas that become the source of inspiration for our projects. In 2011, we established a platform for interaction with specialists in intellectual systems and brain studies. In recent years, issues of machine learning and the possibilities of artificial intelligence were constantly brought up in our discussions. The expectations for machine learning systems are extremely high, and we are interested in rethinking them from a cultural perspective.

We thought about the question of fundamental changes to the human environment: of a “second nature” involving interrelated technologic processes that a person is plunged into from the moment of birth. These processes become increasingly autonomous — machines cease to be fully guided by human commands, instead they constantly adapt to changes of their external and internal environment. And this is just the beginning!

My curatorial research developed in collaboration with Austrian artist Thomas Feuerstein. Together we visited the neuroscience department of the Kurchatov Institute, the research center of Kaspersky Lab and the Center for Consciousness Studies at Moscow State University’s Philosophy Department. We engaged with specialists in cyber security, neural networks, philosophy of mind and neurolinguistics.

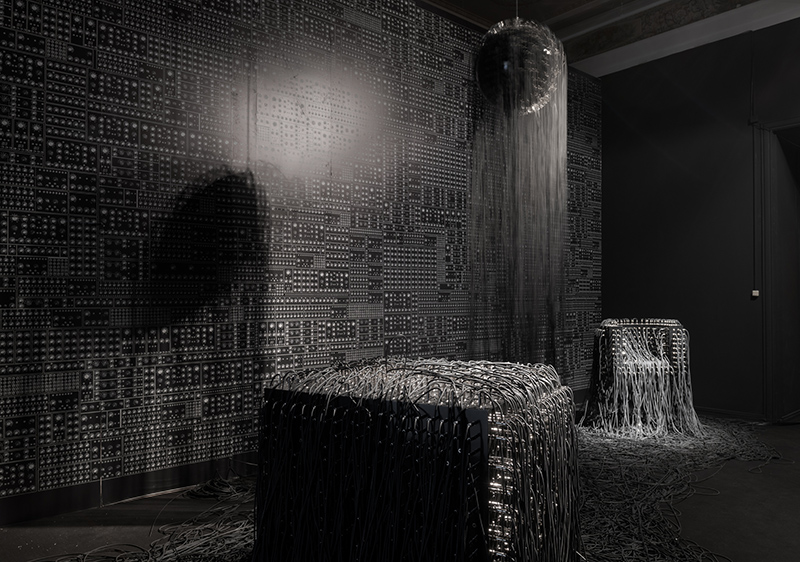

Out of these dialogues the idea to rethink technologic “daemons” emerged. Historically, people have inhabited an outer world with various unseen autonomous presences: whether they are animistic spirits, Antique daemons, monotheistic angels, devils or demons. Nowadays we are dealing with more and more complicated technical objects whose behaviour we can’t predict. This analogy, of course, is not new: “daemons” are background processes in UNIX-based operating systems. Acting unnoticed, they enable the smooth functioning of the operating system. Computers are “animated” in the slang of modern IT-specialists as well: system administrators “dance with tambourines” around computers like the shamans of Siberia, at least at the level of semantic metaphor.

Scientists, writers and philosophers of the last century — from science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke to “hauntologist” Mark Fischer, from the founder of cyberpunk William Gibson to the classic author of technology studies, Gilbert Simondon — all parallelise science and magic, hypothetical artificial intelligences of the future with gods and demons from the past.

We pushed this dialogue forward. In contemporary art there are few works dedicated to this perspective that also use the most up-to-date possibilities of modern technology. We attempted to choose the deepest works that reflect on our current situation — critical, inventing new methods of interaction with machines, or demonstrating a real flight of futurological imagination. Many of the works were produced specially for the exhibition and in collaboration with Russian scientists.

We arranged the artworks in three main groups based on their approach:

- The invention of new mythologies;

- Creation of autonomous communities among technical systems that function without human participation — “technocenoses”;

- Auto-evolving works that explore reactions to their environment and learn to be in it.

You put a lot of effort into engagement with the public with this exhibition, both in terms of explanation and experimentation in the Art&Science Incubator. How have visitors reacted to the exhibition? What kinds of discussion about artificial intelligence has resulted?

We were quite surprised by the depth of engagement with this exhibition. Visitors often immersed themselves deeply in the context, sometimes spending up to several hours in the exhibition. They tried to hunt down not only the artistic message of the works, but also to understand some of the scientific principles lying behind neural networks, for example. We also received a lot of interest from the popular media, including major national news channels.

One question that is often posed about the role of AI is as a creator: what if artificial intelligence pretends to become an artist? The work of Jon McCormack is, among other things, dedicated to rethinking of this issue — his “Niche constructing robot swarm” produces sheets of paper covered with paint. The artwork here is the algorithm that guides the robots and the drawings are simply artefacts: by-products of the algorithm’s functioning.

Of course, one may regard these sheets of paper as “found objects” and declare them the work of art, but then the finder himself becomes its creator. Yet we are unable to say that the machine is the creator — to achieve this, we need them to acquire their own judgement and free will. The Swedish/British philosopher Nick Bostrom considers this will happen inevitably.

Scientists who worked on this project embraced our ideas as well: they expressed a wish to push ahead with further collaborations. So the project is not finished when the exhibition concludes. The Moscow Institute of Steel and Alloys invited us to create an Art-Science Incubator that will produce new interdisciplinary projects. We also plan to publish a book which, aside from the exhibition documentation, also includes scientific articles on contemporary AI issues as they relate to the exhibition.

Your Foundation LABORATORIA Art&Science promotes collaboration between artists and scientists. How do you get both groups to work together successfully? What makes for a good collaboration between artists and scientists?

From the very beginning, LABORATORIA was conceived as a meeting point for artists and scientists. A space that would give them opportunities to create shared language and a platform for interaction. We are not a factory, each project is a kind of “haute couture” — what’s most important for us is the direct exchange of ideas and to allow every participant to work equally. Our goal is to achieve common understanding between representatives of two different cultures.

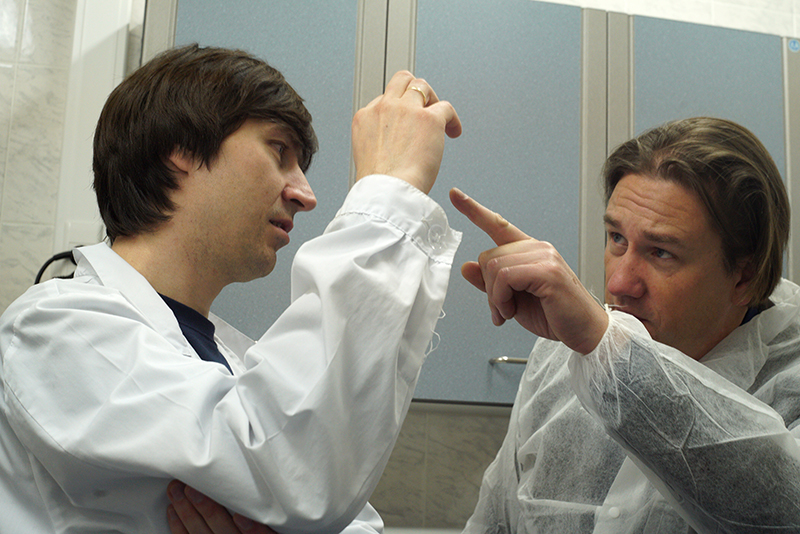

The “Borgy and Bes” project by the artist Thomas Feuerstein which was created in collaboration with the iPavlov research team is vivid example of such an interaction: the artist aimed to learn something new. To do this, he set up a series of interesting challenges for the scientific researchers and they responded. So the project is simultaneously a technological work of art and a scientific experiment.

I always try to make the interest in collaboration highly symmetric: artists do not use scientists as the “executives” of their creative ideas, scientists do not regard artists as the “illustrators” of scientific ideas.

Daemons in the Machine celebrated LABORATORIA’s 10th anniversary. What are your plans for the foundation over the next 10 years?

The future of our project is in overcoming the restraints of the exhibition format. We plan to hold museum exhibitions in future, but our major focus is on the creation of interdisciplinary intellectual platforms that we hope will become sources for innovative new projects. Within these platforms, students and researchers of various scientific and scholarly fields will join interdisciplinary art projects — just like our Art&Science Incubator — under the guidance of artist and scientist.

Technological art is becoming increasingly complex and science-driven. It’s already difficult for museums of contemporary art to create large-scale projects and then keep high-tech artworks persistently functioning.

Over the last 10 years we have developed new methods to establish and grow Art-Science collaboration. These include: the infusion of an artist into a scientific context and of a scientist in art; transposition: preparation and transformation of an artwork using scientific methods; tertiary observation: reaction of artists against scientist’s attitude to their Art-Science collaboration.

Now we want to apply these methods and create not only exhibition projects, but interdisciplinary experimental platforms.

We want to share our vision with those who have similar interests and values, as there are only a few of them in Russia! That is why we want to share our experience and developments with colleagues all over the world, and are glad to show our projects in different countries. We are interested in people for whom “interdisciplinary” isn’t just a buzzword, but a practical reality: those who, like us, believe in the possibilities of Art-Science synthesis.

Demons in the Machine ran from 5th October until 11th November 2018 at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, Petrovka 25, Moscow.

About the Author

|

Daria Parkhomenko is a curator and art historian based in Moscow. She is the founder of LABORATORIA Art and Science foundation (since 2008). Follow LABORATORIA on facebook. Jon McCormack is an Australian-based artist and researcher in computing. He is also the founder and Director of SensiLab and currently an ARC Future Fellow. Follow Jon on twitter |

|---|---|

Website

LABORATORIA

sensilab.monash.edu