This post discusses a speculative design project that questioned the role of technology within complex social issues like gender inequality. Drawing from feminist theory and linguistics algorithms, this project culminated in a research device that monitored the spoken ‘gendered language’ within its vicinity and revealed these patterns back to users in real time.

This device was implemented in a variety of settings and assessed through participant interviews and documentary film. In addition to serving as a heuristic learning tool to generate more complex discussions about gender identity, this device explored what additional value can be gained when turning quantitative data into a qualitative experience.

As a masters student in 2015, I had read Catherine Malabou’s essay called ‘What should we do with our brain?’ and became hooked on this question, especially as an action-oriented design provocation. Given our contemporary understanding of the way our brain is shaped by our experiences, interactions and environments–what are we then obligated to do with that knowledge? For me at that time, I was really interested in exploring this prompt in terms of combatting a negative side effect of our brain’s natural ability to pick up on patterns and make associations: implicit bias.

The issue of inadvertently reinforcing problematic biases in the age of AI is now well documented in popular media and there are more and more initiatives dedicated to mitigating this problem at large scales.

However, for this project, I was interested in understanding how implicit bias might operate at the personal scale of an individual and within their interpersonal relationships. Would it be possible to use technology to make this unconscious mental process more explicit within an everyday context?

My own experience with gender bias had been largely subtle and language-based. With that starting point, I dove into some linguistics research about gendered language. In my search, I found an open-source “Gender Guesser” at hackerfactor.com that “that determines an author’s gender by vocabulary statistics” , with up to 80% accuracy. This tool was developed based on the findings of a study that determined strong associations between certain keywords and the sex of an author.

As a knee-jerk reaction, I was very skeptical of this algorithm. While I was aware bias exists in words used to describe males and females and words associated with men and women, I was less comfortable with the simplistic idea that people themselves could be predictably categorised into one of two groups based purely on the words they used. However, when I tested this tool with emails and articles and even my own writing, I was surprised to find how often it accurately analysed the text. I was left feeling motivated to interrogate this phenomena a bit further and wanted others to experiment with it as I had, but in a more every day context.

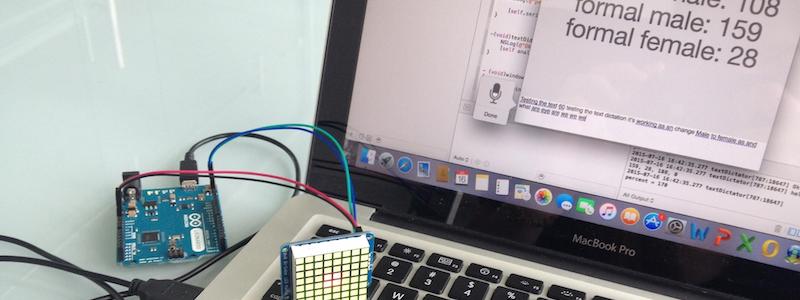

So, I combined this tool with the speech recognition software on my laptop, making it possible to have live speech fed through this algorithm. Then with a little LED light indicator that flashed green for masculine style speech, orange for neutral, or red for feminine speech, the levels of underlying gendered key words that were being used in a conversation (or picked up from television or the radio) could be revealed back to users in real-time.

To test how people would engage with this object, I would go to my friends’ apartments and have a two course meal, while everyone was getting familiar with the device. Later, I conducted a series of interviews to further unpack their experiences. Each interview revealed insights into their unique understandings of the complexities of gender identity and intersectionality.

Initially, I was a bit shocked by how engaging this basic prototype–later nicknamed the “GenderTron”– seemed to be in early testing. Most of the people who encountered it were really fascinated by this device and extremely curious to interact with it. Usually their first instinct was to try to manipulate the colours by announcing words that they thought would trigger a change (ie “war, sports, dogs, aggression” etc. or “children, love, kittens” etc.)

While this spontaneous gender performance was entertaining, it also quickly and explicitly revealed individual’s underlying stereotypes about extreme masculinity and femininity through a playful interaction with this device. There were also moments where participants engaged in self reflection when changes to the colours were unexpected during casual conversation (such as a female frequently using male-patterned speech, or–especially–males using female-patterned speech).

These discrepancies were often explained away through context-specific reasoning for example “if I’m talking about work, it will likely be more masculine” or, “well when we’re talking about emotions, it tends to go female” or “[it would be interesting to take this] device on a date to see if differences become more extreme” With this device, everyone was forced to acknowledge the many other factors that might be influencing an individual’s gender identity. Importantly, they also vocalised and discussed their assumptions about these stereotypes. It seemed as though, in seeing conflicting “evidence” before their eyes, this device didn’t allow people to settle for a simple, binary or innate explanation of differences in gender expression.

For example, Femke, from the Netherlands, was pretty sure that her “Dutch bluntness” might actually register as masculine.

Another friend, Khaleelah, pointed out that, though she considered herself to be very aware of implicit bias, there was a productive difference between having knowledge of this area and having one’s attention drawn to it in the moment.

This project was done in 2015, just before transgender issues became a frequent talking point in british media and politics. In just four years, conversations about gender have become more mainstream, and a part of everyday consciousness in ways they were not at the time of this project. It’s possible that the interactions with this object would now change, or take on new meaning in today’s context. However, something consistent within this timespan is that conversations about gender identity can often get heated. People are often fixed in their opinions in this area. What was amazing to me about this GenderTron research, while extremely small in scale, was that it was a transformative learning experience on a personal level. Through engaging with this object, a handful of my cisgender friends had different, more nuanced, more curious and more playful conversations about gender than I had been able to have with them before.* What enabled these conversations to transcend the usual roadblocks, was the seemingly neutral object coding their words: they weren’t putting forward their ideas to another person with all the judgment and potential arguments that might come with them. Furthermore, for my friends, this object had the disarming quality of the authority of quantitative research behind it. Therefore the direction of inquiry was firmly targeted within oneself and personal life experience, rather than the data. It was fascinating to witness the ways that conversations and conceptions about gender were re-shaped by simply adding this speculative object into the mix.

Now even four years later, as I embark on my PhD, I’m still interested in these questions. Rather than automating tasks and simplifying complex information for us, how we can use technology to do just the opposite? How can it help us draw attention to our own automatic (or implicit) biases? How might it surface and reveal these usually invisible patterns back to us in a compelling way so that we can pay better attention to the complex forces shaping who we are?

*This small-scale study focused on a small group of cisgender people, with whom I had had previous conversations about gender. I am aware that in another context, engaging with this speculative object could be triggering or invalidating for someone if their language patterns were identified inaccurately.

About the Author

|

Hannah Korsmeyer is an Assistant Lecturer in the Design Department at MADA, Monash University. She is a member of the MADA XYX Research Lab, which investigates the relationship between gender and place. She is also a member of WonderLab, where she is part of a PhD cohort researching “design and learning.”. Follow Hannah on twitter |

|---|---|