Can we ever really know what it would be like to be an artificial artist? SensiLab Director Jon McCormack discusses the implications and provocations of a world where AI Artists become major players in human culture.

This is a transcript of a talk given at the Royal Society of Victoria in March 2019 and broadcast on ABC Radio National as part of the Ockham’s Razor series in May 2019.

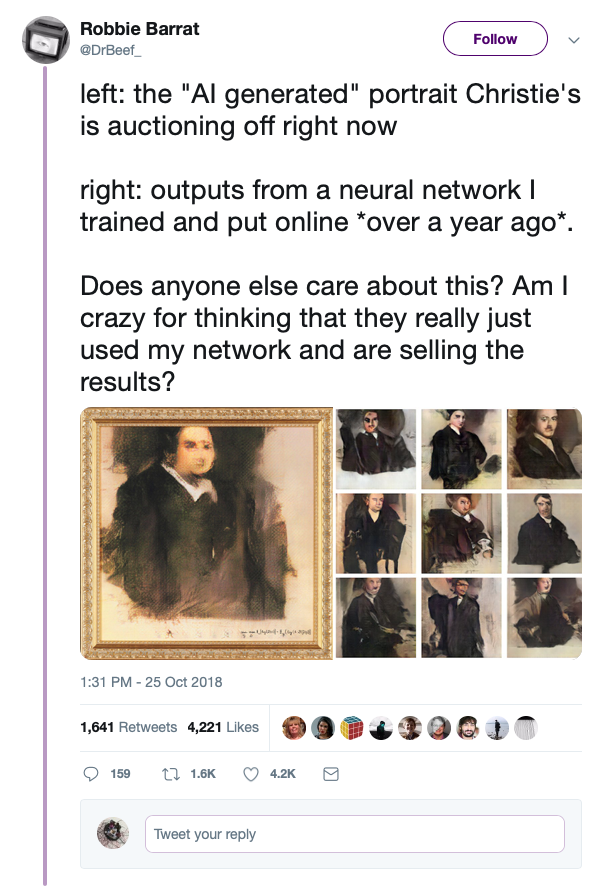

In October last year, an auction at Christies made headlines around the world when “a work of art created by an algorithm” was sold for around $600,000 Australian dollars — more than 40 times the estimated price. The work in question, titled Portrait of Edmond Belamy was one of a group of portraits of a fictional family created by a Paris-based collective called Obvious.

The three members of Obvious had backgrounds in Machine Learning, Business and Economics. They had no established or serious history as artists. Their reasoning for producing the works was to create accessible art that showed what is possible with the current wave of artificial neural network algorithms.

The portrait was generated using a popular neural network technique known as Generative Adversarial Networks (or GANs). Neural networks, based on a highly abstracted and simplified model of biological neurones, learn patterns based on observing many examples of those patterns. And it turned out that Obvious had relied on software written by a 19 year old open source developer, Robbie Barrat, who did not receive credit for the work, nor any money from the sale. In turn, Barrat relied on code and ideas developed by Artificial Intelligence researchers and companies like Google. Ethical concerns were raised about Obvious being the authors of a derivative work generated using open source code largely written by others, even though Obvious were legally entitled to use it under its license terms and conditions.

In fact, it is relatively easy for anyone to download the software for free and make their own fictional portraits. In the research lab where I work, it took us about 30 minutes to create our own portrait series that looked very similar to the work that sold at auction for over $600,000.

To generate images, these generative adversarial networks, these GANs, need to be trained on thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of images of a similar style to what you want the neural network to generate – analysing all of these images so it can learn to imitate them. Typically the training images come from on-line public databases, often drawn from art museum collections as was the case for Obvious’ work.

The generated images, while different from any individual training image, have distinctive characteristics and features from the training images. And of course those characteristics and features arise from the creativity of the human artists who made them.

In a similar vein, a recent headline in the Guardian proclaimed, “Warner Music signs first ever record deal with an algorithm,” with the story describing an Artificially Intelligent music app, Endel, that is expected to generate 20 new albums in the first year of its recording contract. The Beatles only released 12 studio albums over their eight-year career.

So it seems that algorithms are now commercially accepted as creative authors and that art collectors and record companies are prepared to pay generously for their prolific talents. And few aspects of the human cultural landscape are immune from this algorithmic revolution: we’ve seen film scripts, poetry, dance performances and internet celebrities all generated by artificially intelligent algorithms.

The idea of automating the production of creativity to an algorithm raises all kinds of fascinating questions. Foremost is why would we want to automate something so distinctively human?

Making art — being an artist — is a joy. It is something that people want to do. People create art for personal satisfaction, not just to become rich and famous, and in fact the vast majority of artists are neither rich nor famous. And as audiences for art, we value the experience of communication between people, of understanding the imperfection of art and being human through the fragility of human expression embodied in art. We don’t seek the “perfect” work of art then, instead through art we learn about being human, we connect emotionally, physically and socially with the artist and their process of making art.

If a machine can effectively simulate these properties of human art, would we feel the same about art? Would we be ok with being, in essence, fooled by an artificial intelligence into believing it understood what it means to be human?

Art in its contemporary form is not just the production of novel artefacts but the way of life and lived experience that accompanies this making. It encompasses a social dimension that surrounds the activities of artists and audiences. Creativity, in the view of people like John Dewey, was grounded in social experience and personal change, not the production of novel objects.

But this nuanced understanding of art’s meaning has been tempered by a rise in the primacy given to the individual power of the mind or brain as a generator of novel ideas and artefacts. This is a convenient view because we can replace “mind or brain” with an AI and before you know it, an algorithm is the author of a highly priced work of art or a breakthrough music album. In our on-line contemporary culture, where sound and image are increasingly experienced digitally and mediated algorithmically via a smartphone or similar device, who can tell if your media is real or artificial? And as long as we like it, who cares?

An algorithm has no lived experience, no body, no desire to make art or to be an artist. Any fragility or imperfections can be resolved in a software update.

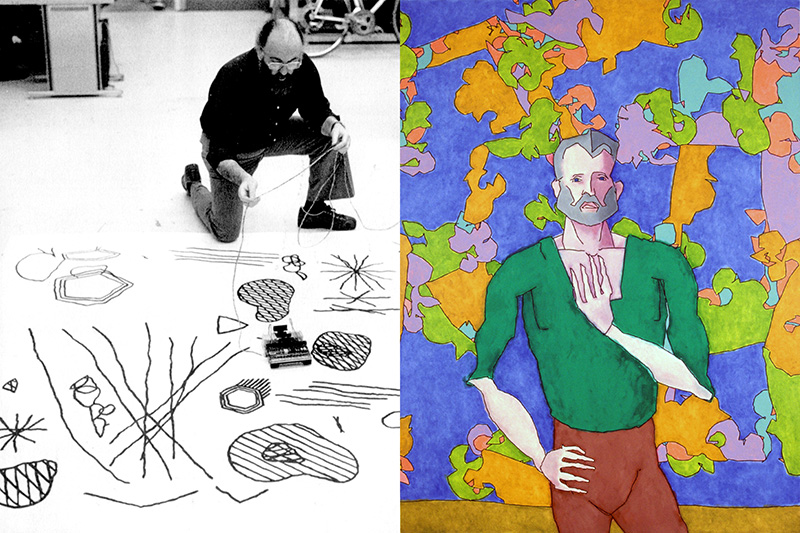

Relationships between algorithms and art have been around for a long time. Ada Lovelace is famously known as one of the first people to record ideas about computer creativity in the nineteenth century. People have been using algorithms to make visual art and compose music for over half a century. The artist Harold Cohen, who died in 2016, spent most of his working life in pursuit of creating an autonomous software painter known as AARON, and while AARON’s work was well received as art, it typically sold for less than 1% of the price fetched for Portrait of Edmond Belamy. What has changed?

One crucial difference between Cohen’s work and Obvious’s efforts is in the claims made about the software. Cohen, who wrote most of the software himself, was clear that AARON was not creative in the sense that humans are creative. Obvious, on the other hand, played on the emerging anxiety and misunderstanding about the current “AI revolution,” pushing the idea that their downloaded software was artificially intelligent and autonomously creative. That it was the artist.

But can a software program be considered an “artist” if it lacks the independent intention to make art or to be an artist?

Human autonomy — typified by free-will — includes the ability to decide not to make art or to be an artist. Software programmed to generate art, deployed across server farms and data centres worldwide, has no choice but to generate. It lacks both the personal autonomy and the intention found in human art.

But could AI force us to change our understanding of what art is and what it means to be an artist? Certainly technology has changed and influenced our view of art in the past. Photography gave us the ability to instantly capture a moment with a visual realism and fidelity that rivalled the best human painters, along with the capacity for mechanical reproduction. Art changed in response, moving away from literal representations to communicating things that photography or film could not. Paintings’ lack of mechanical reproducibility gave the art object a special aura that secondary representations, such as a photograph, lacked. But eventually these new technologies of photography and film were assimilated into the category of art, and today we see all kinds of “new media” in art museum collections.

This was an unprecedented and momentous change, but it pales in comparison to what the potential of Artificial Intelligence might bring to how we understand artists and art.

Beyond the technological improvements that will be required, the bigger questions surround the social, cultural and political currency under which non-human intelligences are created. Do you want a world where your cultural experiences are almost entirely determined by an algorithm? Is it really a good thing to be provided with only what you consider to be — or what you have being trained to know as — the most perfect music, art and culture, synthetically curated and generated specifically for you, based on the statistical machine learning of Silicon Valley’s biggest and most profitable companies?

Just as a machine cannot know what it is like to be a human, we cannot know what it is like to be an artificially intelligent artist.

Further Listening and Reading

Listen to the original broadcast (broadcast date: 26 May 2019)

See the paper presented at EvoMUSART 2019 on this topic: Autonomy, Authenticity, Authorship and Intention in Computer Generated Art

About the Author

|

Professor Jon McCormack is the founder and Director of SensiLab and currently an ARC Future Fellow. Follow Jon on twitter |

|---|---|

Website

sensilab.monash.edu

jonmccormack.info